Consciousness

Consciousness is the subjective experience accompanying our existence. It can be defined as "what it feels like to be something", though the concept is notoriously hard to pin down for people who don't intuitively grasp what is being referred to. Consciousness is closely related to the concept of qualia, which are the components within a conscious experience.

Realism and Terminology

A core property of the definition of consciousness given above is that it doesn't solely refer to a material or computational process. The belief that this type of consciousness exists is usually called consciousness realism, with the opposing view being called illusionism. However, while illusionists generally dispute the existence of a fundamental, non-material aspect of our existence, they often still use the term "consciousness" to refer to the observable computational process in the brain instead (i.e., "consciousness is whatever makes us utter the sounds /ˈkɒnʃəsnəs/"). Notably, the same is almost never done with the term "qualia", which is generally understood to refer to the non-material component only. Thus, the realist perspective tends to treat the terms "consciousness" and "qualia" as almost synonymous, whereas the illusionist perspective tends to re-define "consciousness" as a non-fundamental process and deny the existence of qualia.[1]

Throughout this wiki, "consciousness" and "qualia" are mostly used interchangeably, but it's worth keeping in mind that both terms are often received differently by a general audience. For example, the name "Qualia Research Institute" implies that QRI studies consciousness through a realist lens, whereas "Consciousness Research Institute" would not communicate a position either way.

Qualia Varieties and Phenomenology

Qualia varieties are often classified by the five input channels see, hear, feel, smell, and taste. However, while these channels do constitute five classes of qualia, any such categorization is necessarily incomplete. Many phenomena, such as moods, thoughts, tiredness, or non-bodily pleasure do not neatly fit into any of these categories. Moreover, applying equanimity makes it possible to change the valence of qualia while leaving their information content mostly unchanged.

A better analogy for consciousness might be of an inherently spatial structure like a sheet of paper on which the brain "paints" qualia. Whereas the classical view postulates a discrete number of qualia varieties, the paper analogy suggests that the state space (i.e., the set of all possible qualia) is vast, corresponding to the set of all possible drawings. Frequently experienced qualia (like auditory or visual qualia) correspond to frequently recurring patterns, but such patterns still permit numerous variations corresponding to subtle differences in how a sound or visual scene is perceived. Moreover, many qualia varieties may only ever be experienced during intense meditative states or under the influence of psychedelics.

Note that the valence of a moment of consciousness is a function of how the entire sheet is painted. (See also Consciousness as a musical instrument.) Thus, while specific inputs tend to be represented by high or low valence qualia, there will always be exceptions – e.g., you may recall an instance in which you didn't enjoy your otherwise favorite activity, or conversely, in which you didn't mind performing an otherwise unpleasant task. This dependence of valence on mood and context can be considered another reason why consciousness research is important: a gears-level understanding of how valence is constructed in the brain may ultimately allow for much more effective interventions than are possible today.

Causality

The link between consciousness and causality is the subject of significant and ongoing debate, usually under the label Mental Causation.[2] This question is crucial since it determines whether qualia can be used to draw conclusions about the brain. For example, if consciousness were epiphenomenal, studying qualia could reveal no information about the brain, and if it were non-physical, it couldn't be matched to any known physical phenomenon.

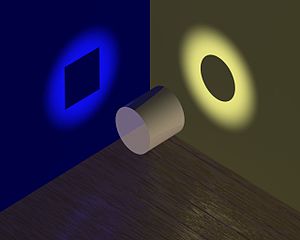

QRI's position can be described as Dual-Aspect Monism (see graphic to the right), which states that the universe consists of a single substrate of which consciousness and physics are two aspects. Under this view, all qualia have a precise physical analog in the brain with an identical causal profile. Thus, whenever consciousness causes you to perform an action (e.g., the qualia of itching making you scratch your arm) the physical analog of this qualia must be responsible for the same effect. This view is the basis for much of QRI's research.

The Study of Qualia

Due to the causal efficacy of consciousness discussed in the previous section, studying qualia can reveal properties about the brain. A complementary principle is Qualia Structuralism, which states that the physical analog of qualia has regularity and structure. Thus, one may not only collect a list of facts about the nature and function of qualia but also uncover principles that explain many phenomena at once.

The practice of using psychedelics or meditation for such a study is known as psychonautics. Psychonautics can be considered analogous to studying extreme physical situations, which is a valid (and perhaps necessary) approach to determining their underlying laws. That said, note that there is no principled restriction of such analyses to exotic states; any underlying laws or principles will apply equally to room-temperature consciousness.

The following is an incomplete list of concepts that are commonly discussed in the context of a systematic study of qualia. In general, note that the phenomenal character of an experience is more important than its semantic content.

- The state-space of a qualia variety, such as color or smell

- Qualia valence, both global and local

- The geometry of an entire moment of consciousness

- Tracer effects

- Local geometrical patterns, such as wallpaper symmetry groups (see also Symmetrical Texture Repetition)

- Flickering effects and their particular frequency

A particularly noteworthy psychonaut is Steven Lehar, who has developed a theory of visual processing based on a decades-long study of visual qualia, primarily at room-temperature consciousness. Steven Lehar has been included in the QRI research lineages and has given a two-hour presentation of his theory on the QRI YouTube channel. His resonance-based model is an example of Nonstandard Computation, complementing QRI's belief that Standard Computation cannot support consciousness.

Binding

Binding refers to the process or mechanism that combines different qualia such that they exhibit an extent of unity. Global Binding refers to the presence of different qualia within the same conscious experience; e.g., a smell and a tactile sensation can be perceived simultaneously, even if they don't seem connected. Conversely, Local Binding refers to the appearance of different qualia as single percepts within a conscious experience; e.g., the sound of a bell may be perceived as a single conscious element, despite being comprised of a spectrum of sounds with varying pitch and timbre.

Global Binding

- Main Article: Binding Problem

Global Binding is one of the six subproblems of consciousness, and the one that QRI tends to emphasize the most. Unlike local binding, global binding seems to be a discrete property, in the sense that any two qualia are either bound together (i.e., appear as part of the same conscious experience) or not bound together (i.e., appear as part of two different conscious experiences), with no middle ground. QRI has proposed a unique solution based on topological segmentation of the electromagnetic field,[3] which is a rare physical mechanism exhibiting sharp, frame-invariant boundaries. The proposal has profound implications for the computational architecture of the human brain and is the primary reason QRI subscribes to the Electromagnetic Hypothesis.

Local Binding

Examples of local binding are ubiquitous within everyday consciousness: virtually every visual scene is immediately partitioned by the brain into discrete objects. Thus, whenever you perceive a regular object like a chair, bottle, or phone, this is an instance of qualia being locally bound together. Note that, unlike with global binding, local binding results in only a partial causal disconnect. For example, a visible crack in a glass jar will primarily affect how you view the jar itself, but it can still have a nonzero causal effect on the scene as a whole.

The impact of local binding can be difficult to appreciate due to the lack of comparison – in general, one doesn't perceive visual qualia without local binding. However, exceptions to this rule occur whenever one fails to recognize an otherwise familiar object. In such cases, the (delayed) moment of recognition is usually accompanied by a noticeable shift in perception. There is also a condition called Visual Agnosia, which may be interpreted as a failure of local binding on all but the smallest scales. People affected with this condition usually report having normal vision but may have trouble identifying everyday items and are generally incapable of recognizing faces.[4] For example, the patient discussed in the previous citation had several photographs of people (including himself) on his wall but was only able to recognize a few of them, and only due to distinct features of their (facial or scalp) hair.

Local binding has an analog from neuroscience in figure-ground perception, and locally bound groups of visual qualia may be analogous to the concept of a gestalt from Gestalt Psychology.

Resources

- PrincipiaQualia – the short book by QRI co-founder Michael Edward Johnson that has been foundational in shaping QRI's research philosophy and agenda.

- Qualia Computing: How Conscious States Are Used For Efficient And Non-Trivial Information Processing – a video by QRI president and co-founder Andrés Gomez Emilsson covering the basics of qualia computing.

- Don't forget the boundary problem! How EM field topology can address the overlooked cousin to the binding problem for consciousness – the academic paper about QRI's solution to the Boundary Problem by Andrés and Chris Percy.

- Paradigm-Shifting Qualia Research Methods: How to Take Exotic States of Consciousness Seriously – another video specifically on psychonautics.

- Taking Monism Seriously – a blog post on dual-aspect monism by Mike Johnson.

- Guide to Writing Rigorous Reports of Exotic States of Consciousness – QRI's guide on how to get the right type of information about of psychedelic experiences.

References

- ↑ Dennett, D. C. (1988). Quining qualia. In A. J. Marcel & E. Bisiach (Eds.), Consciousness in Contemporary Science. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Robb, D., Heil, J., & Gibb, S. (2023). Mental causation. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/mental-causation

- ↑ Gómez-Emilsson, A., & Percy, C. (2023). Don’t forget the boundary problem! How EM field topology can address the overlooked cousin to the binding problem for consciousness. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 17, 1233119.

- ↑ Sacks, O. (1985). The man who mistook his wife for a hat and other clinical tales. Summit Books. pp. 13-14.